We are yet facing another wave of Facebook posts of fake news where sunscreens are considered “unsafe” or “cancer causing due to nanoparticles”. This blog hopes to bust the misinformation and present the evidence. For busting myths of “spray-on sunscreens” see earlier blog (below this article).

What are nanoparticles?

Nanoparticles are fine particles in the range of 100 and 2500 nanometers. Nanoparticles are in between the size of bulk molecules (such as a red blood cell) and the size of an atom.

Nanoparticles are not new. They have been used since the 9th century in Mesopotamia when artisans used these to generate a glittering effect on the surface of pots. This lustre is due to the film containing silver and copper nanoparticles in the glassy matrix of the ceramic glaze.

Why are nanoparticles used in sunscreens?

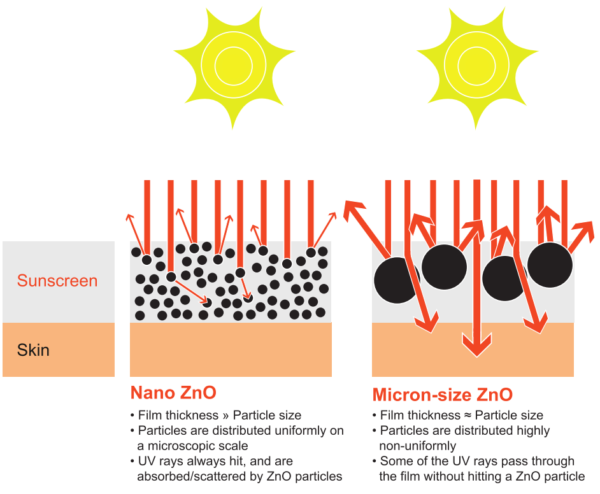

Bulk forms of zinc oxide and titanium dioxide have been used for decades. Their main disadvantage is that they are visible on the skin as an opaque layer and hence the comment, “pale as a ghost”. This has been the main criticism of the older generation sunscreens. This undesirable visual effect has been addressed by reducing them to the size of nanoparticles. When used in this form, these oxides cannot be seen on the skin, but they still retain their UV-blocking properties.

Why the hype about nanoparticles?

Similar to the hype on Facebook about spray-on sunscreens, there has been concern that nanoparticles in sunscreens can be absorbed into the circulation causing cancer.

How safe are sunscreens?

The available evidence suggests that sunscreens have an excellent safety profile and are without significant absorption. This website by the Australian Government Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) concluded that titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles do not penetrate the underlying layers of skin, with penetration limited to the stratum corneum (outermost layer of the skin), and neither of them is likely to cause harm when used in sunscreens. I highly encourage a read:

Are there any downsides to sunscreen?

Yes. Some individuals are allergic to sunscreen This ranges from mild to severe. Most of the UV filters known to be contact sensitizers such as para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), amyl-dimethyl-PABA, or benzophenone-10 are now rarely used in sunscreen manufacture. Oxybenzone (benzophenone-3), is the most frequent cause of sunscreen-induced photoallergic contact dermatitis. However, the estimated rate of contact sensitization to oxybenzone-containing products is <0.1 percent to 1.0 percent.

Some UV filters (eg, octinoxate, oxybenzone) have been found to have estrogenic effects in animal models. In one study, oral oxybenzone induced an uterotrophic effect in immature rats. However, when studied in humans, there is no evidence that sunscreens alter the sex hormones in humans.

How to spot fake news?

Whilst I have done my best to present scientific data, this fake news of “sunscreens causing cancer” will be one of a million other fake news yet to come. A while ago when news was delivered in print, authors had to think long and hard before publishing news as print was expensive.

Here are some tips on spotting fake news:

- Check the source: Someone’s personal opinion on Facebook, a personal video on Facebook, The Onion, The Daily Mail, The Sun, these are not considered scientific evidence.

- Look for concomitant headlines from the source: If you see a subsequent headline from the same author citing that “Elvis is alive” or that a “cure for cancer has been found”, it would give you an indication of the source’s integrity.

- Check the credentials of the author: Are they an expert in the field? What are their educational qualifications?

- Check references from the article: If there are none, question why that is. If there are, which reputable journal are they published?

- Check the quality of the written article and domain name: Articles loaded with obvious spelling errors, grammatical error or domain sites ending in “.ru or .co” is a red flag.